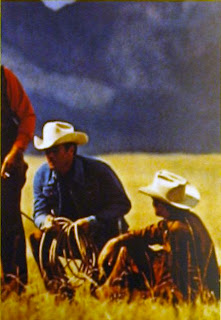

Many girls have experienced an infatuation with the horse. This romance

takes many forms, from early play, through fantasy and desire, and perhaps to

the act of riding. The horse, a

symbol of beauty, power, freedom and magic, can be an object of identification

or serve as a protector. The

girl's favorite possessions surround her, including a plastic horse collection,

horse show ribbons, saddle, and her diary. The bedroom is a shrine to the

horse, and is evidence of girls' search for self-definition.

Tackling what exactly the appeal of

ponies really is, while powerfully conveying her passion for them, Susannah

Forrest has written a beautiful book about her own equine obsession, while

casting her eye over the role horses have played in popular culture. Opening

with descriptions of her Falabella obsession, and of anxieties she had as a

child that she might grow too tall to ride a Derby winner, you quickly know

you’re in the hands of a true addict.

Weaving affectionate memories of

ponies she has loved and lost, Forrest is most concerned with the role it

played from the Industrial Revolution onwards, although she takes the reader on

a brisk canter across the centuries, pointing out horse meat was a staple part

of Stone Age man’s diet, but that it wasn’t until the Renaissance that

equestrianism took on significance as a literary form.

Forrest isn’t joking when she

subtitles the book an equine obsession, because her descriptions of the ponies

who have trotted into her life are dedicated and lengthy. More compelling for

the general reader is her examination of why young girls, in particular, love

ponies so much. The golden age of girls and ponies was born in the early

20th century when horses were to give girls an independence that was quite new.

It was during the First World War that women tasted, in large numbers, the

intoxicating independence experienced from the back of a horse; their brothers

and fathers and husbands away, upper-class women in particular developed a

taste for riding astride to hounds with the same bravery as their male

counterparts, and perhaps a bit more skill.

By the Thirties and Forties, horses

and ponies had won their place within the hearts and minds of little girls. A

whole literary genre grew up around them, started by Muriel Wace, writing under

the name Golden Gorse, who declared “There is no greater pleasure in the world than

riding a good horse.”

The Pony Club was born in 1929, and

by the mid-Thirties, every girl in the country had a crush on National Velvet,

the eponymous heroine of Edith Bagnold’s novel, immortalised by Elizabeth

Taylor on screen. A thirst for novels with names like Silver Snaffles

grew; Joanna Cannan was one of the finest of these writers, although the horsey

heroine without equal was undoubtedly the show jumper Pat Smythe, who travelled

the world with her horses, combining an unequalled equine talent with an

appetite for adventure and glamour.

This truly was a golden age of riding, but so potent was

the power of those ponies that by the end of that century, a government drugs

adviser identified “equine addiction syndrome.” Horses, she writes, once “gave girls a corner of the

world where they were freed from the burden of being ‘girls’, where they could

be ambitious and brave and strong.”

~The unique roles ponies can play in the lives of girls to

make them feel strong and independent~

One of the most interesting sections relates to work by

the Swedish psychologist Sven Forsling, who set up a rehabilitation centre for

truanting girls who’d fallen into drug abuse and sexual exploitation. It had a

racing stables, where the girls were expected to look after their own horses,

which made them feel brave. The strongest evidence of this comes from one of

these girls, who, racing her horse around the track for the first time,

declared “Yes! I am divine!”

*Susanna Forrest, If Wishes Were Horses: An Equine

Obsession

*Clover Stroud, The Telegraph, March 2012